26 August 2020: Articles

Post-Traumatic Retroperitoneal Hematoma Caused by Superior Rectal Artery Pseudoaneurysm

Challenging differential diagnosis, Unusual or unexpected effect of treatment, Rare disease

Karleigh R. Curfman1ABEF*, Mieka P. Shuman1ABEF, Kimberly M. Gorman2ABEF, Wesley B. Schrock3ABCD, Paul G. Meade1ABEFDOI: 10.12659/AJCR.924529

Am J Case Rep 2020; 21:e924529

Abstract

BACKGROUND: Pseudoaneurysms are a known pathology commonly recognized after disruption of the vascular wall leads to the development of a hematoma. Although pseudoaneurysms are common, occurrence in the location of the superior rectal artery is exceedingly rare, has been documented in the literature only 7 times, and can be extremely dangerous. Patients can present with vague abdominal complaints, pain, gastrointestinal bleeding, and development of hematomas, and can progress to hemodynamic instability related to hypovolemia. This phenomenon requires swift recognition and patient management, as well as stabilization, to achieve desired results and minimize morbidity and mortality.

CASE REPORT: We report the case of a 79-year-old man who presented after minor trauma with gastrointestinal bleeding and was diagnosed with a retroperitoneal hematoma. Although he was stabilized and discharged, conventional angiography diagnosing and treating his causative superior rectal artery pseudoaneurysm was not completed until a second traumatic event resulted in recurrent presentation with worsened symptoms and retroperitoneal hematoma enlargement.

CONCLUSIONS: Superior rectal artery pseudoaneurysm is a rarely-reported phenomenon, usually occurring after a traumatic event. It can lead to significant anemia, hypovolemic shock, blood transfusion, and other serious consequences. It can be difficult to diagnose given its location and obscurity. However, upon diagnosis, swift treatment is recommended, for which a variety of both surgical and endovascular approaches have been employed to prevent exsanguination.

Keywords: Aneurysm, False, Angiography, Anticoagulants, Hematoma, Retroperitoneal Space, Gastrointestinal Hemorrhage, Mesenteric Artery, Inferior

Background

Pseudoaneurysm can be common within the human anatomy, in which a perivascular hematoma develops due to disruption of the vascular wall layers and results in a communicating hematoma [1]. This entity, although common in other vessels, is extremely rare in the superior rectal artery (SRA) and has been reported in only 7 published cases [2–8]. Although several of the prior reports were related to traumatic events and the others were caused by unique, varying factors, their presenting symptoms and treatment modalities were strikingly similar and successful. Here, we describe the presentation and hospital course of a 79-year-old man on therapeutic anticoagulation, who presented several days after a ground-level fall with complaints of abdominal pain, constipation requiring manual disimpaction, and subsequent gastrointestinal bleeding. At that time, he was diagnosed with a large retroperitoneal hematoma, stabilized, and discharged. It was not until after the patient’s second fall approximately 4 weeks later, for which he presented with worsened complaints and hematoma enlargement, that a bleeding SRA pseudoaneurysm was identified as the cause of his symptoms. Here, we discuss the hospital course and patient management and present a literature review of presentation, diagnosis, imaging, and recommended treatment options and strategies for management of SRA pseudoaneurysms.

Case Report

Approval to publish this case report was obtained from the facility’s Institutional Review Board prior to investigation and reporting. We describe a 79-year-old man who initially presented to the Emergency Department (ED) with acute onset of abdominal and rectal pain, as well as 1 episode of rectal bleeding. He reported that he had recently fallen 3–4 days prior to presentation and had been constipated, requiring manual disimpaction, which caused bleeding. Of note, he was on warfarin for a history of atrial fibrillation; thus, due to his symptoms and history, he underwent computed tomography angiography (CTA). His CTA was significant for a large, poorly-defined, retroperitoneal hematoma extending from the right abdomen into the pelvis, without obvious active bleeding (Figures 1, 2). Because a large hematoma was identified, his anticoagulation was held, serial abdominal examinations were performed, and his hemoglobin was serially trended. On presentation, his hemoglobin was 13.0 gm/dL; however, over the next 24 h it decreased to 8.5 gm/dL. The patient became tachycardic and thus was transfused with 2 units of packed red blood cells and 1 unit of fresh frozen plasma for an international normalized ratio of 1.7. His hemoglobin was then stable after transfusion for several days and remained stable after resumption of warfarin, and he was then discharged.

The patient was scheduled for repeat CTA imaging in 6 weeks, but 4 weeks after discharge he returned to the ED with similar complaints of abdominal pain, constipation, and urinary retention. His hemoglobin was stable upon his return, but he unfortunately signed out of the ED against medical advice prior to receiving any further interventions. Two days later, he returned after another fall, with complaints of worsening abdominal pain, distention, constipation, and urinary retention. His hemoglobin was relatively stable; however, his CTA was repeated, with new concerns for enlargement of the known retroperitoneal hematoma from the previous size of 9.0×4.5 cm to 9.9×7.4 cm, as well as signs of active bleeding and a questionable pseudoaneurysm (Figures 3, 4). He underwent pelvic and inferior mesenteric artery (IMA) angiograms with Interventional Radiology (IR), where a large blush off of the SRA was identified, suggestive of a pseudoaneurysm (Figure 5).

Several attempts at embolization of the tiny feeding branch were unsuccessful; therefore, coil embolization of the SRA was performed (Figure 6). Following the procedure, the patient’s hemoglobin and vital signs were stable within baseline parameters. He was discharged home on post-procedure day 2 and continued on warfarin. He has yet to follow-up on an outpatient basis with either the Trauma or Interventional Radiology services. However, on evaluation in the ED for separate complaints, repeat imaging was performed, which demonstrated a slight decrease in his retroperitoneal hematoma to 9.0×7.0 cm and his hemoglobin level was stable at baseline.

Discussion

Pseudoaneurysm is a perivascular hematoma that develops as the result of a partial disruption of the vascular layers, which maintains communication with the vascular structure [1].

The significant difference distinguishing pseudoaneurysm from aneurysm is the involvement of wall layers – a true aneurysm involves all vessel wall layers, while a pseudoaneurysm is only associated with partial wall layer involvement [1]. There are various known causes of pseudoaneurysm, most importantly infection, inflammation, and trauma [2]. In addition, there can be significant complications associated with pseudoaneurysms, including rupture, massive hemorrhage, adjacent structure compression, and infection [2]. Thus, given the serious risk of complications, especially with an associated rupture mortality risk of nearly 50%, early diagnosis and immediate appropriate management are essential [2]. For diagnosis, imaging must be performed, for which the criterion standard is conventional angiography [1]. However, due to limitations in personnel and facility capabilities, pseudoaneurysms are often diagnosed via other imaging modalities such as ultrasound or contrast-enhanced computed tomography [1]. Another benefit of diagnosing pseudoaneurysm via conventional angiography is that conventional angiography can concomitantly be therapeutic [1]. Recommendations for management include angiographic embolization and/or stent placement, as well as the possible need for surgical intervention [2].

Initially, there were concerns for colonic ischemia and infarction associated with angiographic embolization, which have since been resolved [9]. Prior angiographic interventions did not gain significant popularity due to the use of nonsteerable wires, and resulted in inadvertent dissections and embolization of marginal arteries, with subsequent ischemia [9]. With the development of steerable guidewires, the super-selective delivery of small embolization coils to vessels distal to the marginal arteries could be achieved, which significantly lowered the colonic ischemia and infarction risk [3,9]. Proceeding with surgical intervention is indicated when angiographic treatment modalities fail or if the patient is hemodynamically unstable [1]. There are several surgical options that can be used to achieve hemostasis, including pseudoaneurysm resection with bypass, ligation, or resection of the involved organ [1].

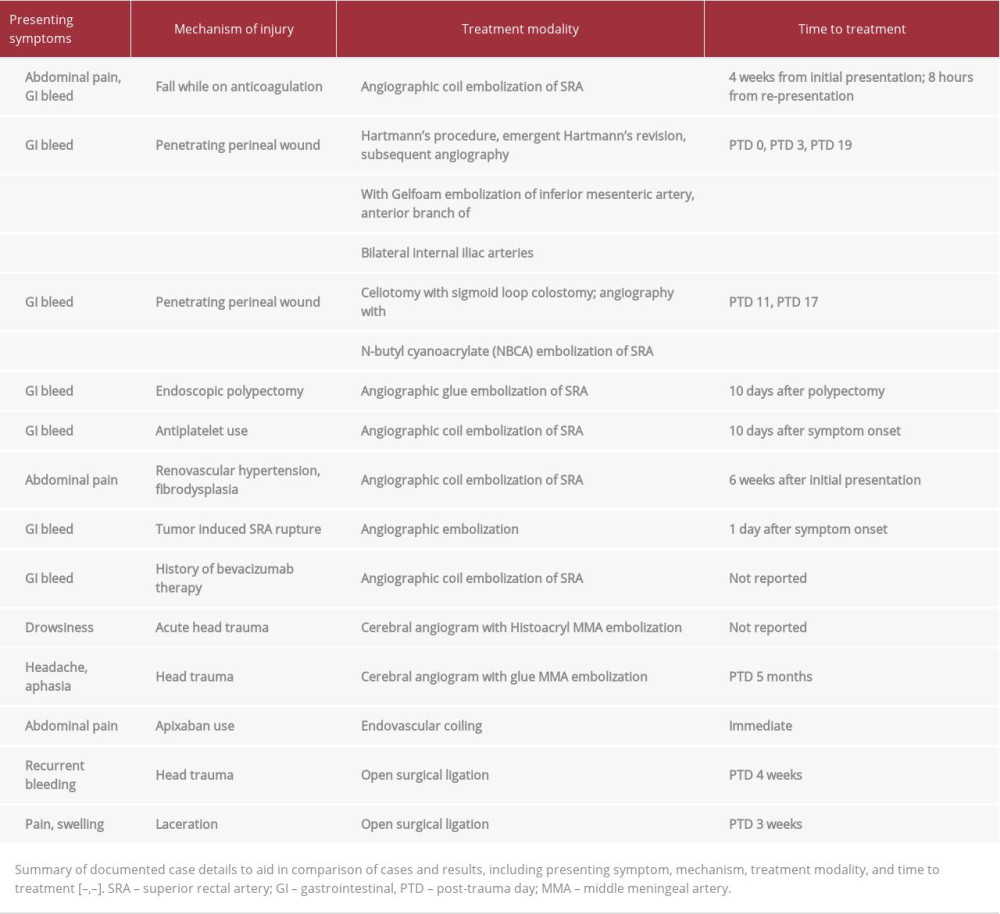

The occurrence of pseudoaneurysms throughout the body is often reported, especially after vascular or cardiac interventions; however, involvement of the SRA is rare. Our thorough literature search found only 7 other documented cases – 3 were related to trauma (2 were secondary to direct rectal injury, 1 occurred after colonoscopic polypectomy) [2–4], and the remaining 4 were atraumatic. One patient presented with bleeding, likely related to clopidogrel use, another was reported with a history of renovascular hypertension secondary to fibrodysplasia, 1 patient was recognized following malignant tumor erosion into the vessel, and 1 patient was identified after bevacizumab use for sigmoid adenocarcinoma [5–8]. Although the reported cases had various causes, their symptom complexes were similar. Six of the known cases presented with a chief complaint of lower-gastrointestinal bleeding [2–5,7,8], and the remaining patient presented with complaints of worsening abdominal pain [6]. In addition, although the causes varied, the management plans in each of these cases, as well as our own, followed the previously stated recommendations. In all of the reviewed cases, the patients were able to be safely treated via angio-graphic embolization, though 2 cases initially underwent open surgery [3–8]. In the published cases, the patients achieved hemodynamic stability and improvement in symptoms following intervention, without any reported pseudoaneurysm-related mortalities. As in the present case, the appropriate diagnosis could not be identified on initial presentation, and development of pseudoaneurysm may have been a delayed complication of the initial event. Regardless, delay in identification and management of a pseudoaneurysm can lead to worsening and possibly life-threatening bleeding. Table 1 summarizes the reported cases, their presenting symptoms, mechanism, treatment modality, and time to treatment, if available, for comparison and ease of review.

Finally, in addition to the rarity of this phenomenon occurring in the SRA, there have been multiple other rare occur-rences seen in other sites throughout the body. Inadvertently-discovered occurrences have been reported in the peripheral arteries as a known complication of percutaneous interventions, but there are other unique locations and occurrences that have occurred without interventions, similar to our case. Some of these other rare cases included involvement of the middle meningeal artery, superior mesenteric artery, occipital artery, and palmar arch [10–14]. Such as the cases referenced in our SRA pseudoaneurysm review, these patients presented with varying symptoms, mechanisms, time to diagnosis, and treatment modalities. Their presenting symptoms were most commonly related to pseudoaneurysm location, and included drowsiness, headache, aphasia, pain, recurrent bleeding, and swelling [10–14]. The mechanisms also differed, with both traumatic and nontraumatic causes (acute head trauma, chronic development after head trauma, apixaban use, knife laceration) [10–14]. Similarly, treatment and time to treatment varied between endovascular and open approaches – immediate and months after initial injury, respectively. These treatments included cerebral angiogram with Histoacryl embolization of the middle meningeal artery, cerebral angiogram with glue embolization of middle meningeal artery, endovascular coiling, and open surgical ligation [10–14] (Table 1). Consistent with our SRA pseudoaneurysm review, the mechanism, presentation, timing, and management of these pseudoaneurysms varied, but all reported cases required appropriate identification and treatment to prevent further serious complications, bleeding, rupture, and death.

Conclusions

Superior rectal artery pseudoaneurysms are extremely rare but serious, with dire potential consequences. Due to the paucity of reported occurrences in the published literature, supporting evidence and recommendations are scarce, although existing recommendations appear to be effective. In the 7 previously published SRA pseudoaneurysm cases, and in our own, management techniques have yielded excellent results with minimal adverse effects and no mortalities. Given these findings, the success evidenced by angiographic management in our case and the significant adverse effects that are risked by delaying treatment, we are in agreement with the current recommendations and strongly support intervening and actively managing SRA pseudoaneurysms without delay.

Figures

References:

1.. Choi PW, Pseudoaneurysm rupture causing hemoperitoneum following rectal impalement injury: A case report: Int J Surg Case Rep, 2019; 55; 28-31

2.. Kim KJ, Seo JW, Kim YS, Traumatic pseudoaneurysm of the superior rectal artery with recurrent lower gastrointestinal and pelvic extraperitoneal bleeding: Importance of pretreatment recognition: J Korean Soc Radiol, Jan; 72(1); 29-32

3.. Iqbal J, Kaman L, Parkash M, Traumatic pseudoaneurysm of superior rectal artery – an unusual cause of massive lower gastrointestinal bleed: A case report: Gastroenterology Res, 2011; 4(1); 36-38

4.. Zakeri N, Cheah SO, A case of massive lower gastrointestinal bleeding: Superior rectal artery pseudoaneurysm: Ann Acad Med Singapore, 2012; 41(11); 529-31

5.. Janmohamed A, Noronha L, Saini A, Elton C, An unusual cause of lower gastrointestinal haemorrhage: BMJ Case Rep, 2011; 2011; bcr1120115102

6.. Vieira M, Sampaio S, Lopes J, [Endovascular management of a ruptured pseudoaneurysm of a rectal artery]: Rev Port Cir Cardiotorac Vasc, 2012; 19(4); 221-24 [in Portuguese]

7.. Shirahata A, Satou S, Matsumoto T, Superior rectal artery pseudoaneurysm caused by rectal cancer: J Anus Rectum Colon, 2014; 67(6); 408-12

8.. Li CC, Tsai HL, Huang CW, Iatrogenic pseudoaneurysm after bevacizumab therapy in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer: Two case reports: Mol Clin Oncol, 2018; 9(5); 499-503

9.. Baig MK, Lewis M, Stebbing JF, Marks CG, Multiple microaneurysms of the superior hemorrhoidal artery: Unusual recurrent massive rectal bleeding: report of a case: Dis Colon Rectum, 2003; 46(7); 978-80

10.. Paiva WS, de Andrade AF, Amorim RL, Traumatic pseudoaneurysm of the middle meningeal artery causing an intracerebral hemorrhage: Case Rep Med, 2010; 2010; 219572

11.. Umana GE, Cristaudo C, Scalia G, Chronic epidural hematoma caused by traumatic intracranial pseudoaneurysm of the middle meningeal artery: Review of the literature with a focus on this unique entity: World Neurosurg, 2020; 136; 198-204

12.. Guirgis M, Xu JH, Kaard A, Mwipatayi BP, Spontaneous superior mesenteric artery branch pseudoaneurysm: A rare case report: EJVES Short Rep, 2017; 37; 1-4

13.. Woods M, Moneley D, Occipital artery pseudoaneurysm: A rare complication of head trauma: EJVES, 2014; 27(4); 34-35

14.. Schoretsanitis N, Moustafa E, Beropoulis E, Traumatic pseudoaneurysm of the superficial palmar arch: A case report and review of the literature: J Hand Microsurg, 2015; 7(1); 230-32

Figures

In Press

06 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.942937

12 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943244

13 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943275

13 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943411

Most Viewed Current Articles

07 Mar 2024 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.943133

Am J Case Rep 2024; 25:e943133

10 Jan 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.935263

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e935263

19 Jul 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.936128

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e936128

23 Feb 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.935250

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e935250